How to make chopsticks-compatible bowls

When I first came to the US, I was surprised by the popularity of Asian food here, especially rice and especially in university cafeteria. Though rice seems to be widely accepted, people here still seems to have a strong preference for knives and forks over chopsticks in terms of utensils. I don’t blame them given chopsticks mainly relies on friction, which is a very different mechanism from forks and spoons which they are accustomed to. I prefer chopsticks of course. What I want to discuss here, is mainly due to how uncomfortable/awkward I found using chopsticks with these Amazon Basics porcelain bowls. You see - usually when I lay down utensils like spoons and chopsticks, for hygienic considerations, I don’t put them on the table - I simply just place them IN the bowl or on the plate, and they tend to stay put. But when I came to the US and do the same, my chopsticks fall out of the bowls A LOT.

I am not joking how annoying it is whenever my chopsticks fall out of the bowl onto the ground and I’d need to get a new pair of chopsticks and, sometimes, also clean up the carpet. Some would argue that I can simply put chopsticks on top of the bowl, horizontally. However, this is not a satisfactory solution, simply because chopsticks can easily roll off the bowl given it’s not a stable equilibrium - the gravitational potential is flat - no local minimum. Apperantly a lot of people share my opinion and designed some absurd-looking bowls just to fix this issue (see picture below) (and they also don’t seem to be good designs either).

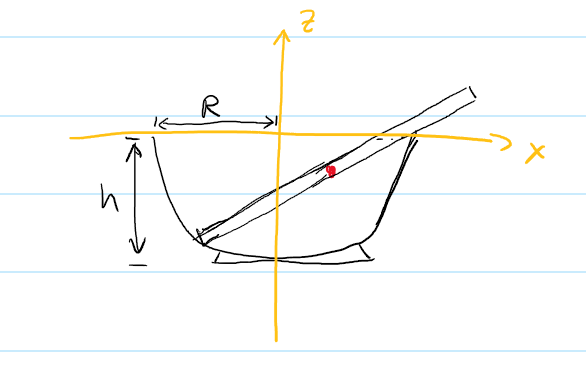

In my opinion, the traditional bowl shape is fine, but determining the exact shape would need a careful analysis on how to keep the chopsticks stable, though not a difficult one. Let’s make a few assumptions to facilitate our analysis. First let’s assume the bowl is empty with only one chopstick with length $L$ in it, and the shape of the bowl should be rotationally symmetric on the z axis. The upper edge should be a circle of radius $R$. And we also fix the height to be $h$ so the upper rim and bottom center of the bowl is fixed and we can focus on the shape. Also when I say shape of “the bowl”, obviously I’m referring to the interior of the bowl, which is the only part that’s in direct contact to the chopstick.

For the chopsticks to be stable, any small displacement from the equilibrum position should result in a force directing back to the equilibrium by definition, which means the equilibrium position should be a local minimum for gravitational potential. Given the symmetry of the bowl, we can just look at a cross section of it that cuts though the center (see graph below). Our task is simple: we just need a good contour of the bowl (i.e. a good $z(x)$) such that the height of the center of mass of the chopsticks $H_{com}(x,z(x))$ has a local minimum. Goes without saying: $z(0)=-h,\, z(\pm R) = 0$.

A little bit of high school geometry gives us

\begin{align}

H_{com}(x,z(x))=z\cdot(1-\frac{L/2}{\sqrt{(R-x)^2+z^2}})

\end{align}

Taking derivative w.r.t. $x$ gives

\begin{align}

H’_{com}(x)=z’-\frac{L}{2}\frac{(R-x)[z’\cdot(R-x)+z]}{[(R-x)^2+z^2]^{\frac{3}{2}}}

\end{align}

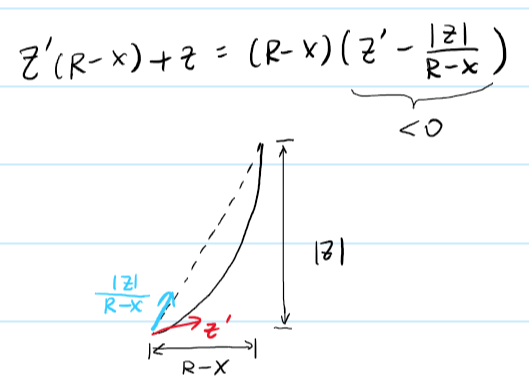

Let’s do a quick sanity check. For a concave bowl i.e. $z''(x)>0$, our intuition tells us the chopstick can never climb up the bowl on the right side i.e. $H'_{com}(x)>0$ when $x>0$ regardless of how long the chopstick is and whatever shape the bowl is as long as it’s concave. Concave condition leads to $z’\cdot(R-x)+z<0$ (an intuitive graphic argument see below), a positive second term and since $z’$ is also always positive on the right side, $H’_{com}$ is indeed always positive when $x>0$.

Thus, now we just need a point on the left side at which $H’_{com}\mathbf{<}0$ and then a local minimum with $H’_{com}=0$ would be guranteed to exist. Examining our expression for $H’_{com}$ above, the first term $z’$ is always negative and the second term has two components $z’\cdot (R-x)$ and $z$ in the numerator, which, combined with the overall negative sign, are both always positive on the left side. As a result, it all comes down to the length of the chopstick, which sets the ratio of the coefficients between the first term and the second term. If the chopstick is short enough, e.g. if $L/2<2R$ i.e. the center of mass of the chopstick is always inside the bowl, then a point near the rim ($x\rightarrow -R$) such that $H’_{com}<0$ is guranteed because $z\rightarrow 0$ and the combined coefficient for $z’$ is $>0$. Motivated by this scenario, we raise these questions: what’s the largest $L$ that a local minimum still exists whiling maintaining the overall shape of the bowl ($z’>0$ while $x>0$ and $z’<0$ while $x<0$), and where’s the local minimum?

Reorganizing $H’_{com}<0$ \begin{align} H’_{com}=(1-\frac{L(R-x)^2}{2((R-x)^2+z^2)^\frac{3}{2}})\cdot z’ - \frac{L(R-x)}{2((R-x)^2+z^2)^\frac{3}{2}}\cdot z \end{align}

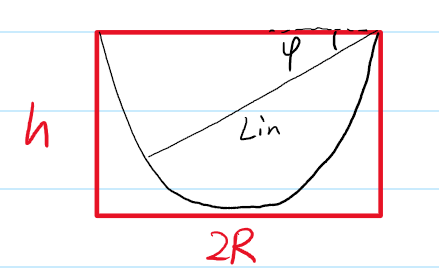

Theoretical limit says local minimum can exist as long as $1-\frac{L(R-x)^2}{2((R-x)^2+z^2)^\frac{3}{2}}>0$ and we could just set $z’ \rightarrow \infty$ at that point and $H’_{com}<0$ i.e. making the wall at that point almost vertical. Rewriting it to look a bit nicer \begin{align} \frac{L_{in}}{cos^2(\phi)} > \frac{L}{2},\;\;\; L_{in}\equiv \sqrt{(R-x)^2+z^2}, cos(\phi) \equiv \frac{R-x}{L_{in}}, \phi \in [0,arctan(\frac{h}{R})] \end{align} Also visualizing the constraints on the size of the bowl, it should not extend to outside of the red box in the graph below.

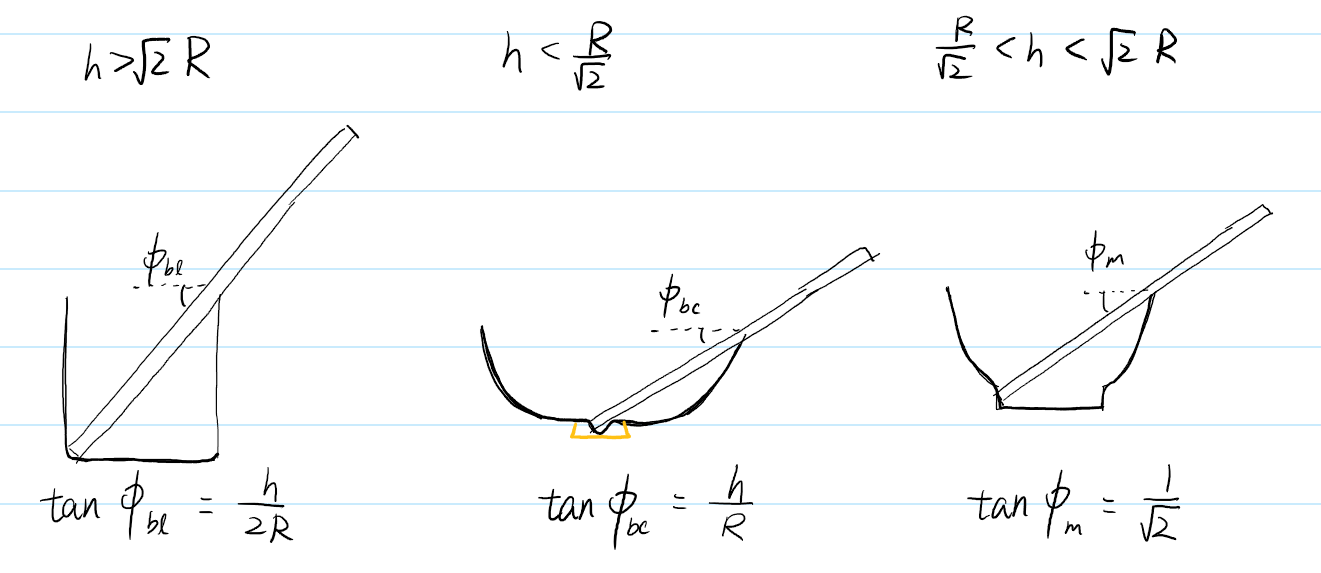

It can be easily observed that to maximize $L_{in}$, the left end of the chopstick should be on the red box, and also $\frac{L_{in,max}(\phi)}{cos^2(\phi)}<\frac{\sqrt{(2R)^2+h^2}}{(2R)^2/[(2R)^2+h^2]}=\frac{L_{in,max}(\phi_{bl})}{cos^2(\phi_{bl})}$ for all $0<\phi<\phi_{bl}$, where $\phi_{bl}=arctan(\frac{h}{2R})$ corresponds to chopstick reaching the bottom left corner of the red box. Thus, we only need to find the maximum of $\frac{L_{in,max}(\phi)}{cos^2(\phi)}$ in the range $\phi_{bt} < \phi <\phi_{bc}$, where $\phi_{bc}=arctan(\frac{h}{R})$ corressponds to chopstick reaching the bottom center. In this range,

\begin{align} \frac{L_{in,max}(\phi)}{cos^2(\phi)} = \frac{h}{sin(\phi)cos^2(\phi)} \end{align}

Maximum is reached at $sin(\phi_m)=1/\sqrt{3}$ and $max(\frac{L_{in}}{cos^2(\phi)})=\frac{h}{sin(\phi_m)cos^2(\phi_m)}=\frac{3}{2}\sqrt{3}h$, i.e. maximum length of chopstick that the bowl could accommendate is $3\sqrt{3}h\approx 5.2h$. The shape of the interior of the bowl would be like this: flat at the bottom until $\phi=\phi_m$ angle where there’s near-vertical wall for some small practical height, and this will be the stable equilibrium point for the chopstick, above that the shape does not matter.

Some readers might notice that $\phi_{bl}<\phi_m<\phi_{bc}$ may not always be possible. Indeed, when $h > \sqrt{2}R$, $\phi_m < \phi_{bl}$. In this case, I’m afraid that in order to accommendate for long chopsticks, the bowl would need to adopt the beaker shape and the stable equilibrium point is reached at the bottom left corner. When $h < R/\sqrt{2}$, $\phi_m > \phi_{bc}$, the optimal configuration would be a small near-vertical well at the bottom center of the bowl. Also, when I said near-vertical, it doesn’t have to be 90 degrees exactly. One can calculate the needed angle by plugging in everything into the $H’{com}$ equation to solve for the slope $z’$ needed.

So to summarize, $L_{max}=f(\phi_{max})=\frac{h}{sin(\phi_{max})cos^2(\phi_{max})}$.

| $h < \frac{R}{\sqrt{2}}$ | $\frac{R}{\sqrt{2}}<h<\sqrt{2}R$ | $h>\sqrt{2}R$ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\phi_{max}$ | $\phi_{bc}$ | $\phi_m$ | $\phi_{bl}$ |

| $arctan(\frac{h}{R})$ | $arctan(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}})$ | $arctan(\frac{h}{2R})$ |

- Only the shape of the interior of the bowl is being discussed here and, of course, more structure on the outer surface can be added for balance and other purposes etc. e.g. the orange support structure in the graph above.

Comments